To read the latest article about Fr. Emil Kubek from Carpatho-Ruysn researcher and author Nick Kupensky click the link below.

No, We Won't Die by Nick Kupensky- Slovo Magazine - Summer 2016

The Kubek Project

The Father Emil Kubek Walking Tour of the West End took place on Sunday, November 22, 2015. Below you'll find a pictorial record of the tour.

Shown above is the souvenir post card which was given to all participants of the tour. This picture shows the West End of Mahanoy City in 1930.

Preparing for the Walking Tour

Pictured above from right to left are: Nick Kupensky, founder of the Kubek Project, Peg Grigalonis, president of the Mahanoy Area Historical Society and Paul Coombe,webmaster and historian.

Eminent Carpatho-Rusyn Historians Visit Mahanoy City on Thursday

Above:A few of the many books written by Paul Magocsi

On the Thursday before the tour two prominant Carpato-Rusyn scholars visited Mahanoy City to experience the Walking Tour with Nick Kupensky, Peg Grigalonis and Paul Coombe. Pictured below are from left to right: Paul Magocsi, Nick Kupensky and Valerii Padiak inside St. Mary's Byzantine Catholic Church.

Professor Magocsi is the world’s leading expert on Carpatho-Rusyn history. He is the holder of the Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto where he has created the most complete library of Carpatho-Rusyn-related scholarship and other materials in the world—a literal treasure-trove for scholars. He is a widely recognized and respected researcher, writer, and teacher, enormously energetic, sharp in terms of his critical thinking. When attending Professor Magocsi’s lectures, be ready to take voluminous notes from the start! His lectures will introduce you to the history of Carpatho-Rusyns from their beginnings to the present day. His style is to present his lecture and then to set aside 30-45 minutes for questions and answers. This lets him cover efficiently what he wants to convey, and then he is open to whatever questions might have arisen during the course of the lecture. Those Q&A sessions, by the way, are as exciting and informative as the lectures. You will definitely acquire a keen understanding of where our people came from and what forces shaped them through the centuries, and you’ll be able to share your new and tremendous body of knowledge with your family and community.

Valerii Padiak is a bright and enthusiastic scholar from Uzhhorod, Transcarpathia—just over the border from Slovakia in Ukraine. Like Professor Magocsi, he has been teaching at the Studium since its founding in 2009. He has also been teaching at the Institute of Rusyn Language and Culture at the University of Prešov. Padiak is steeped in the history and culture of Carpatho-Rusyns originating in Transcarpathia. He is a walking encyclopedia! Among other things, he is a publisher of books on Carpatho-Rusyns, a calling in which he has been involved for many years. He has worked hard developing educational opportunities for Rusyn kids in Transcarpathia, as well, and he has helped Studium participants in the past three years get in contact with their Rusyn roots in Transcarpathia. Padiak strongly encourages the American participants in the Studium to practice their Rusyn, and in his warm and animated way he is happy to encourage even simple conversations over meals in the cafeteria.

Source: The Carpatho-Rusyn Cultural Center

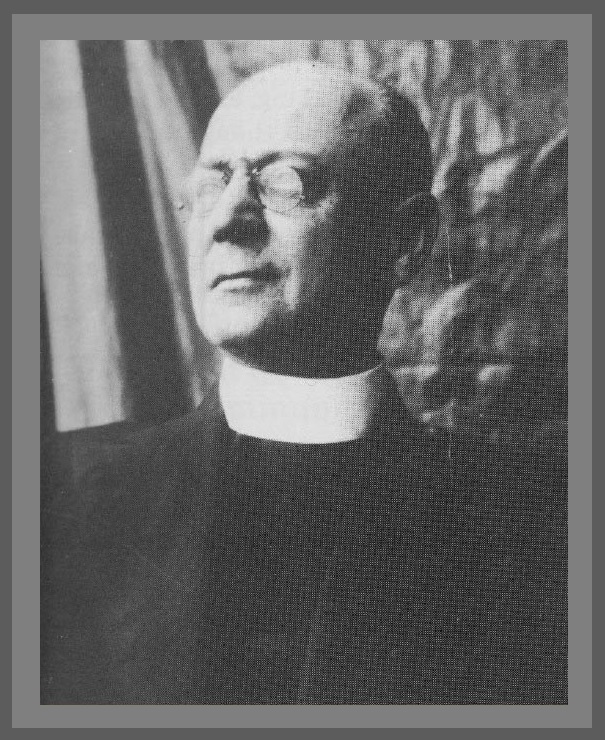

The picture above was given to the historical society by Professor Padiak. Emil Kubek is famous in Eastern Europe. There is an elementary school named for him and classes on his literary works are taught in colleges .

After visiting St. Mary's, professors Magocsi and Padiak toured portions of the West End before arriving at John Smith's Mansion where they were greeted warmly by the owners Michael Cheslock and Gary Senavitis.

Paul Magocsi with Michael Cheslock

Paul Magocsi explains some of the research he has done on the life of John Smith to Michael Cheslock and Gary Senavitis, owners of Smith's Mansion while Nick Kupensky and Peg Grigalonis look on.

At the Red Zone on West Centre Street

Professors Magocsi and Padiak made a stop at the Red Zone along with Nick Kupensky and Peg Grigalonis.

The Walking Tour on Sunday

St. Mary's Byzantine Catholic Church

The icon above is located to your left after entering St. Mary's Byzantine Catholic Church. Note that the Child Jesus is holding a container of anthracite coal.

Nick Kupensky explains the imagery on the ceiling frescos and the stained glass windows. Many of the paintings were done by Father Emil Kubek's son, Father Anthony Kubek.

Recreation of a 1931 photo taken at the dedication of the new church

Photo above is from St. Mary's 100th Anniversary book. Fr. Emil Kubek and John Smith can be seen just to the left of the top center of the picture.

Nick Kupensky reads one of Rev. Emil Kubek's Poems from the porch of St. Mary's Rectory

The West End Cafe

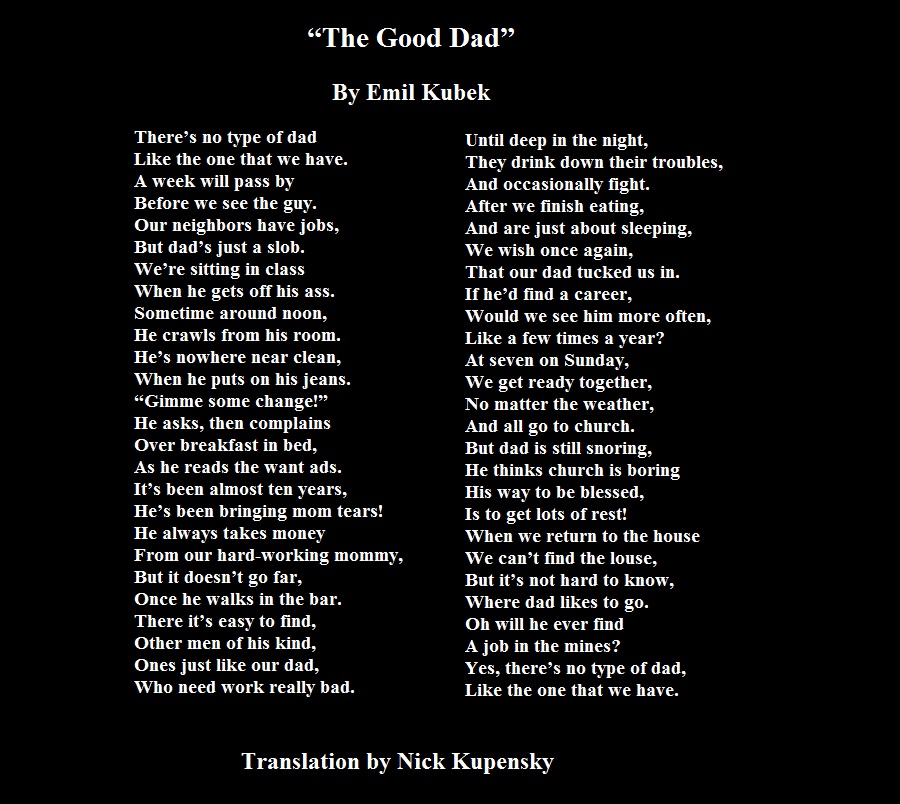

After leaving St. Mary's the tour group of about eighty made their way to Mahanoy Street for a short stop in front of St. Mary's Rectory. The group then walked along D Steet to the front of the West End Cafe, the oldest continually operating bar in Mahanoy City. Nick Kupensky read his translation of the Emil Kubek poem, "The Good Dad". Nick made note of how Father Kubek used humor in the poem which deals with an otherwise sad and serious topic- alcohol use and abuse among the miners of the hard coal region.

The oldest cafe in Mahanoy City is now operated by Bill and Ruth Ann Sedlak Davidson and their son Derrick.

Ruth Ann's parents purchased the cafe in 1958 from the Gudd (Gudaitis) family who had operated the business since the end of prohibition.

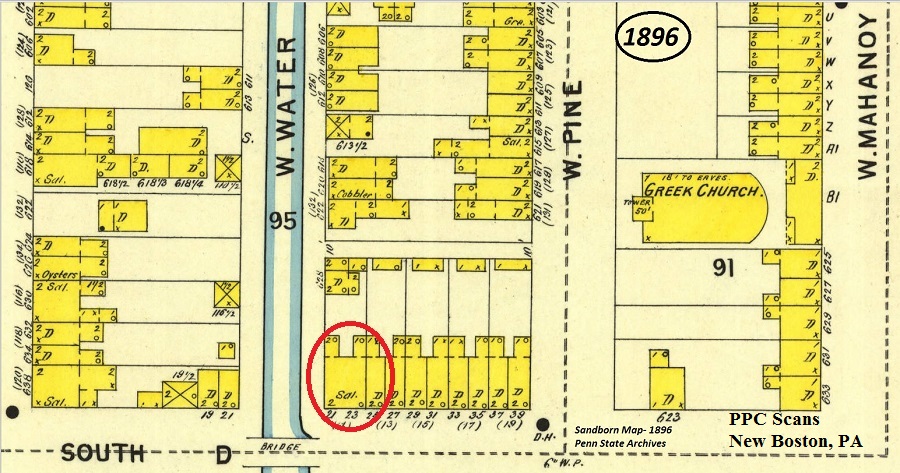

The 1896 map below shows a saloon located at the present site of the West End Cafe.

Note that the majority of the saloons on the map below were located west of Main Street and that the highest concentration is located in the first ward which was heavily populated by ethnic groups from Eastern Europe.The red arrow points to the location of the West End Cafe. The pie graph below shows the breakdown of liquor licenses in Mahanoy City in 1920 just as the Volstead Act ( Prohibition) was about to go into effect.

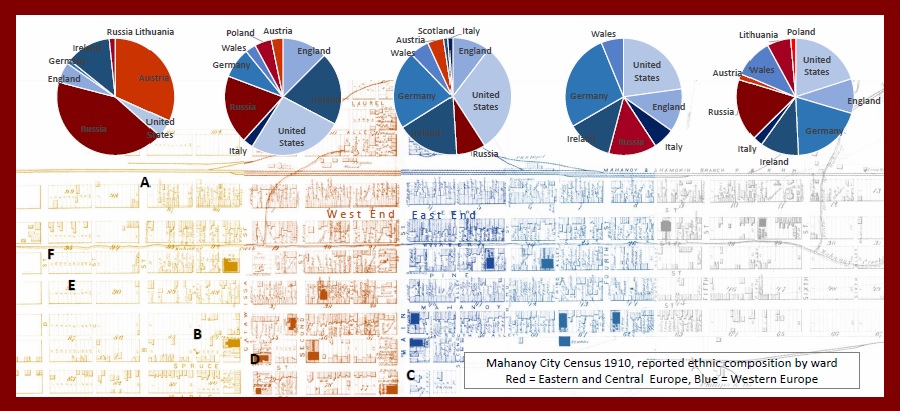

After sampling some boilo inside the West End Cafe the group made their way to the corner of West Railroad and D Street where Erin Frey, a student at Bucknell University and researcher for the Kubek Project, climbed the "cribbin " to address the group about the concentration of the Eastern European ethnic groups who populated the West End in the early part of the 20th century. During Holy Week of 1921 a short story by Fr. Emil Kubek appeared over a period of three days in the Mahanoy City Record American. The title of the story is An Easter Gift and the setting of the story is West Railroad Street. Below is a short excerpt from An Easter Gift.

Excerpt From An Easter Gift

By Rev. Emil Kubek

Translated by Rev. Louis Sanjek - Holy Emmanuel Slovak Lutheran Church

Have you ever seen “a yard of the nations?”

Many of them are to be found on the outskirts of large American cities on a thoroughfare which is neither street nor avenue but an alley. It needs but a glimpse to tell what class of people are living there. For the romantic souls who compose the yard about which I am going to write, there is a lumber yard, the boards of which are occupied from springtime until late in the fall by those optimistic philosophers of the American land, known to the inhabitants as “bums.”

Trains pass the yard every hour, by day and by night – passenger and freight, black diamond and milk express. The earth trembles under their heavy loads and the inhabitants of the yard of nations are in danger of losing their hearing bye and bye.

You don’t find much light between the houses in the yard for the sunshine cannot break through. Light by night is furnished the inhabitants by two small lights placed on the street by an honest-to-goodness borough council. Even this small amount of light is needful, especially after pay day – and for the denizens of lumber yard.

The lumber yard affords a trysting place for sweethearts who come from as far away as East Centre street to speak about the greater things of life, here among the sleepers. Neither moonshine nor electric lights bother them here. Even the dogs of the neighborhood keep quiet for they know the visitors. A more ideal place for the children of cupid you cannot imagine.

From afar you will know everyone who resides in the yard even though it be for only three months. You will know them even in church. The church goers from the alley don’t know how to whisper or to speak in low tones. Because of the noise made by the trains they are accustomed to loud speaking and cannot break the habit. When other people feel it is incumbent to whisper, they almost shout.

In the yard of the nations live eight families, close together, like so many sardines in a box. There are really eight and a half families for our Fedor Bistrica, we might consider a half-family. To place eight and one half families on one lot is no easy task even for Second Alley. But Mr. McMuch is a smart fellow and knows how to accommodate them. They pay, therefore, two dollars less than is demanded for a cleaner place, and that is very important.

The nationalities in the yard represent nearly all of Europe. One family is Polish, one Lithuanian, another Greek, one Serbian, another Slovak, one Niger and two are Italian families. The heads of these families – one from Lombardy and the other from Sicily – married sisters, after much quarreling, and now fail to recognize each other as fellow countrymen.

In the yard you will find thirty-six children of varying ages. In Niger’s family there are seven children. Sometimes entire families are fighting together.

There are many clues in the story to show that the setting is on West Railroad Street. The two big clues are the lumber company and the railroad tracks. The Mahanoy City Lumber Company was located at the end of the 400 block of West Centre Street for many years. In the rear of the main building was the lumber yard on Railroad Street. The proximity of the lumber yard to the railroad tracks may have made it an attractive site for local "bums" and for the hoboes who traveled the rails from town to town. (An area east of the 8th Street Bridge on the north side of the railroad tracks was known as " bums hollow" because of the encampment of vagabonds often found there.) Lest we be critical of the many wanderers who traveled the rails by hopping freight trains and coal cars, we may remember that at this time in American history there was no welfare, no unemployment, no workers' compensation, no social security and no retirement income for most workers.

The 400 block of West Railroad is one likely setting that may have inspired Fr. Kubek in his writing of An Easter Gift. About the time the short story was written, the 400 block was home to ninety resident living in ten houses. The link below will open a PDF files that shows the occupants of the 400 block in 1910. The files shows names, age, country of birth, occupation and address. There are no homes indicated beyond 428 West railroad because the remainder of the block was occupied by the lumber company at 430-438 West Railroad.

1910 Mahanoy City Census- 400 Block West Railroad Street

Bucknell University student Erin Frey, researcher for the Kubek Project.

Erin Frey spent a good part of her summer researching the Slavs of Western Middle Coal Field. Using research gathered from the archives of the Mt. Carmel Item newspaper, Erin compiled a "word cloud" which graphically depicts the perceptions people held about the Slavic immigrants who streamed into coal region communities in the late 1800s and early 1900s. To view the word cloud click on the link below.

To see the complete demographic poster compiled by Erin Frey and Nick Kupensky click the link below.

Poster: The Slavs of Mahanoy City

Almost all of the adult male residents of West Railroad Street and some children as young as fourteen worked in or around the colleries. Over 30,000 miners lost their lives in the anthracite mines of Northeastern Pennsylvania from 1870 to 2000. The account of the death of one of those miners who lived on West Railroad Street illustrates the hazards of deep mining which killed so many and mained and took the health of so many more. The obituary below appeared in The Record American the year after Fr. Kubek's short story, An Easter Gift, appeared. I've underlined portions of the obituary to emphasize themes which were common in many mine deaths.

Some artistic West Railroad Street residents have beautified the "cribbin" across the alley from their home.

A clothesline hook can still be found on a "telepole" near the corner of Catawissa and West Railroad Street. This gem was pointed out to me by Diane Rechuck, a resident of West Centre Street, who also owns property on West Railroad. You can imagine the scene on washday ( Monday) on West Railroad with many "pulley-lines" extending from the homes on the block to a pole, such as the one below near or corner, or to poles placed across the alley on the "cribbin" near the railroad tracks. Women had to be vigilant on washday for the approach of a coal train heading east from the St. Nicholas Breaker. The dust from the coal cars could blacken the day's clean laundry which hung near the path of the approaching coal train.

Anyone who grew up in Mahanoy City knows the name Kaier. Charles D. Kaier established his business in 1862, one year before the borough was incorporated. Kaier is a name associated with a brewery, an opera house, a mansion and numerous local sports teams both amateur and professional.

Many native sons and daughters of the borough may be familiar with Smith's Mansion which stands at the corner of South Catawissa and East Spruce Street. You can't help notice this historic structure as you make the turn to go up the "Pottsy", but few people are aware of the history behind the mansion and the man who built it.

John Smith Biography

Ioann Žinčak was born on July 19, 1863 in Rakovčik, Šariš County, Hungarian Kingdom (present day Slovakia), he moved to Liverpool, England at the age of fourteen, where he changed his name to John Smith. After a number of years learning the shipping industry, Smith came to the United States in the early 1880s, first settled in Boston, then soon after moved to Mahanoy City.

In 1886, Smith was married in St. Michael’s Greek Catholic Church in Shenandoah to Anna Schuster (from Prešov, Slovakia), and the couple would go on to have eleven children together: John Jr., Mary, Augustine, Olga, Anna, Tekla, Ella, Nicholas, Emanuel, Vladimir and Irene.

Smith began his career in Mahanoy City in the hotel business, but it was his grocery stores that helped established his fortune. His first grocery was a small storefront on 63 West Centre Street (now 305 West Centre Street), but in 1891, he relocated one block down and opened a larger operation at 417-419 West Centre Street that included a butcher’s shop, notary, and travel agency. Known for its “store at your door” service, Smith’s was particularly popular among the miners because they made deliveries directly to the coal patches. From 1892 to 1908, the 419-417 property served as the Smith family residence as well, which was was located on the second floor.

...In addition to his role in the creation of St. Mary’s and his reputation as a successful businessman, John Žinčak Smith was also one of the most active and influential Carpatho-Rusyn activists, and his effect on Carpatho-Rusyns throughout the United States can be seen most vividly in his role as the steward of two fraternal organizations: Greek Catholic Union (GCU) and the Russian Brotherhood Organization (RBO).

Nick Kupensky

Note: Smith served as a private banker for many years. Many of his customers were recently arrived Slavic immigrants who needed a mortgage. In 1923 Smith was a major influence in the creation of the American Bank. The American Bank took over the building which was the location of the Union Nation Bank when that bank moved to a new building at 1-5 West Centre Street. The American Bank building still stands at the corner of West Centre and Laurel Street.

This empty lot was the site of the former John Smith Company grocery store at 417-419 West Centre Street. The store was in operation from the 1880s until about 1967.

Smith purchased a printing press for $700 from St. Michael’s Church in Shenandoah, had it installed in Mahanoy City at the corner of South Second and West Water Streets (now Linden and Market), and hired two Rusyn linotypists to get the paper up and running. This paper, the Amerikansky Russky Viestnik (ARV, or the American Rusyn Messenger), would become not only one of the most influential Rusyn-language periodicals in the United States but a crucial medium for the publication and circulation of Kubek’s work.

Nick Kupensky

By the turn of the century, John Žinčak Smith had become the most accomplished Carpatho-Rusyn businessman and community leader in Mahanoy City, and in 1908, Smith moved his family from their modest West Centre Street home to this monumental mansion at the corner of South Main and East Spruce Street. Built at a cost of $40,000, the mansion included fourteen rooms, four chandeliers, wooden cabinets, and a number of stained glass windows . Just as he changed his name from Ioann Žinčak to John Smith nearly 30 years earlier, his move from the predominantly Slavic, Catholic West End to the Anglo-Saxon, Protestant East End symbolized his meteoric rise from his humble origins to the economic elite of the region.

Nick Kupensky

Smith's Mansion

The pictures below are from the inside of Smith's Mansion

John and Anna Smith with ten of their eleven children.

Workers put the finishing touches on John Smith's Mansion - Circa 1908.

Mike Cheslock and Gary Senavitis retreived this section of wallpaper from the Victoria Theatre before its demolition.

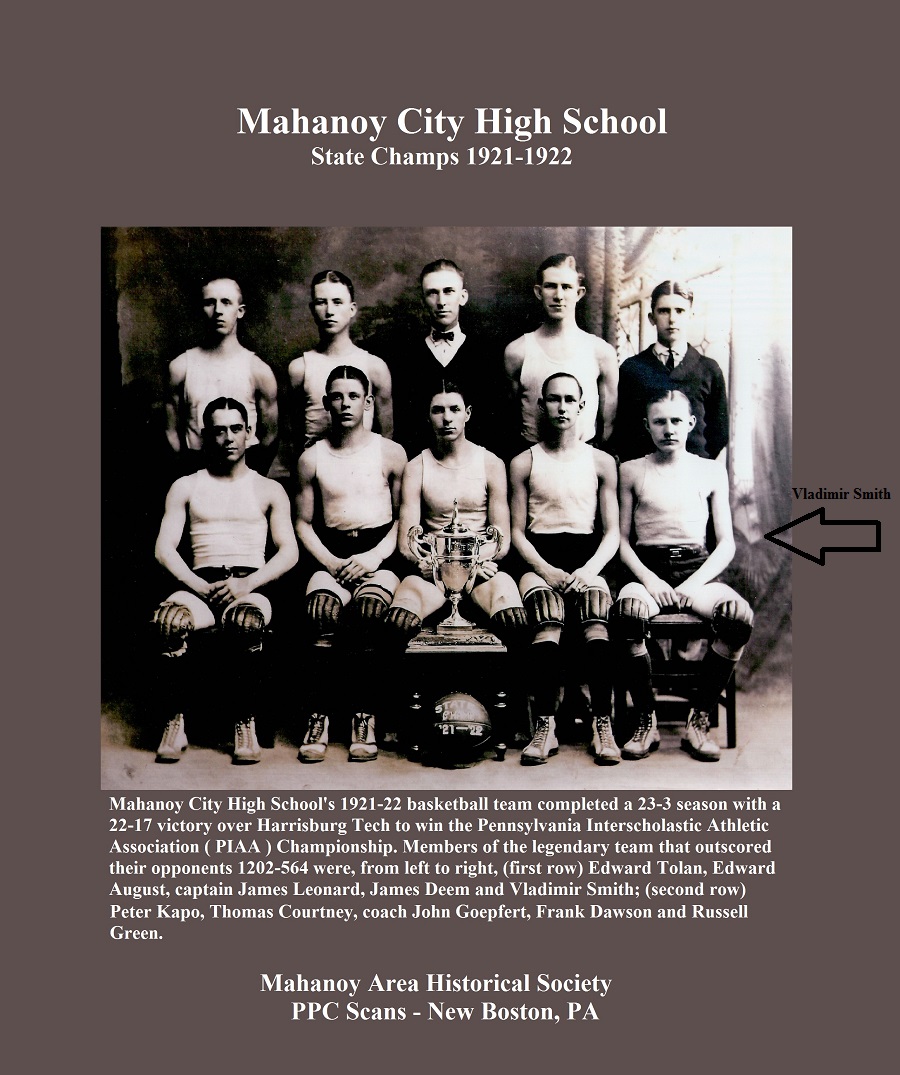

John Smith's son,Vladimir, played on Mahanoy City High's 1922 State Champion basketball team.

At Rev. Emil Kubek's Gravesite

WVIA videographer Ron Andruscavage records the readings at Rev. Emil Kubek's gravesite.

Nick Kupensky reads Emil Kubek's poem, No! We Won't Die !

At St. Mary's Center for the Birthday Party

From left to right above: Nick Kupensky, Martin Kubek and Drew Skitko

Drew Skitko of the Philadelphia Opera Company performs at Rev. Emil Kubek's birthday party. A graduate of Westminster Choir College, Princeton, N.J. , Drew has appeared in numerous stage productions with the Philadelphia Opera, the Westminster Players and at the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival.

Pictured above is the volunteer kitchen staff of St. Mary's Center. Second and third from the left are Margaret Ann Shemansik and Mary Ellen Bias Farnsworth with Fr. Emil's great grandson, Martin Kubek and Father Jim Carroll, pastor of St. Mary's . Mary Ellen, Margaret Ann and the staff prepared an authentic Carpatho-Rusyn meal which reminded many of the attendee's of a meal from "baba's" kitchen.

More Information About the Kubek Project and Links to the Digital Walking Tour

Emil Kubek’s Mahanoy City

Description of Emil Kubek Project

Note: The Kubek Project Walking Tour of Mahanoy City has been scheduled for Sunday, November 22. More information will follow on this web site, and in the Pottsville Republican.

Click here to enlarge The Slavs of Mahanoy City, PA.

Nick Kupensky Interview in Coal Cracker

Kubek Project Web Site and Digital Walking Tour

An English Translation of a Kubek Short Story - 1921

An Easter Gift

by Rev. Emil Kubek

Drawing by Rev. Anthony Kubek

Translated by Rev. Louis Sanjek

Transcribed from The Record American by Erin Frey

Chapter I

Have you ever seen “a yard of the nations?”

Many of them are to be found on the outskirts of large American cities on a thoroughfare which is neither street nor avenue but an alley. It needs but a glimpse to tell what class of people are living there. For the romantic souls who compose the yard about which I am going to write, there is a lumber yard, the boards of which are occupied from springtime until late in the fall by those optimistic philosophers of the American land, known to the inhabitants as “bums.”

Trains pass the yard every hour, by day and by night – passenger and freight, black diamond and milk express. The earth trembles under their heavy loads and the inhabitants of the yard of nations are in danger of losing their hearing bye and bye.

You don’t find much light between the houses in the yard for the sunshine cannot break through. Light by night is furnished the inhabitants by two small lights placed on the street by an honest-to-goodness borough council. Even this small amount of light is needful, especially after pay day – and for the denizens of lumber yards.

The lumber yard affords a trysting place for sweethearts who come from as far away as East Centre street to speak about the greater things of life, here among the sleepers. Neither moonshine nor electric lights bother them here. Even the dogs of the neighborhood keep quiet for they know the visitors. A more ideal place for the children of cupid you cannot imagine.

From afar you will know everyone who resides in the yard even though it be for only three months. You will know them even in church. The church goers from the alley don’t know how to whisper or to speak in low tones. Because of the noise made by the trains they are

accustomed to loud speaking and cannot break the habit. When other people feel it is incumbent to whisper, they almost shout.

In the yard of the nations live eight families, close together, like so many sardines in a box. There are really eight and a half families for our Fedor Bistrica, might consider a half-family. To place eight and one half families on one lot is no easy task even for Second Alley. But Mr. McMuch is a smart fellow and knows how to accommodate them. They pay, therefore, two dollars less than is demanded for a cleaner place, and that is very important.

The nationalities in the yard represent nearly all of Europe. One family is Polish, one Lithuanian, another Greek, one Serbian, another Slovak, one Niger and two are Italian families. The heads of these families one from Lombardy and the other from Sicily – married sisters, after much quarreling, and now fail to recognize each other as fellow countrymen.

In the yard you will find thirty-six children of varying ages. In Niger’s family there are seven children. Sometimes entire families are fighting together.

In the two Italian families there are twelve children. Quite often all are fighting at once excepting those in the laps of their mothers. Children do not go to parents to arbitrate their disputes because more often than not a whipping comes from that quarter. Sometimes the disputes of the neighborhood were brought to the Squire’s office for adjustment but that official became perplexed by the babel of tongues and was compelled to disperse them because all talked at once.

Fedor Bistrica was the only one who did not mix himself in the quarrels of the international yard. He did not have any right to the privilege, for Fedor had neither wife nor children, neiher did he pay full rent. He was the inveterate enemy of all the women and also of the children. Not for the world would he talk to a woman.

Now that I have told that much about Fedor it is my duty to explain the reason for his animosity toward women and children, even though he should bring me to the squire’s office.

Fedor is – years old but looks ten years older. Healthy, robust, but always full of sorrow, a sorrow which has plucked at his heart ever since that day he came to America twenty three years ago. He recalls the days of his youth in that little village in the Carpathians where he was born. What a jolly and happy youngster he was. Always singing in the fields whether ploughing or using the sickle. At the dances he was first. Many a girl felt happy when he spoke to her. He was a good son, too.

Even the parish priest was very much interested in Fedor and desired to send him to the higher schools.

“Vasil,” he said to Fedor’s father, “you have the money to send your son to school. Some day he may become a priest.”

“Thank you, Father,” Vasil would reply, “but I am of the opinion that to be a farmer is no less important than to be a priest. I would rather see him a conscientious, common, every-day man than educated and without conscience.”

Vasil, Fedor’s father, though a young man had much property and only two children. Besides Fedor there was a daughter, Nastja, two years younger than Fedor.

“My property I will leave to my son, Fedor,” Vasil would often say. “My father left it to me and I will leave it to Fedor to take as good care of it as I have taken.” Fedor’s mother was of the same mind as her husband and Fedor prepared for the life of a farmer on his own land.

This love of the land you will find in the heart of every Russian and Fedor was no exception.

Vasil Bistrica was looked upon as the most honest man in the village. He never looked for honors and when his neighbors elected him a justice of the peace he felt called upon to decline the honor. In the church he was a faithful worker and held the office of president of the church council. Everyone in the village loved him but his most intimate friend was his neighbor, Mitrims.

Fedor was a regular visitor at the Mitrims homestead where there was a daughter, beautiful and charming. Three years younger than Fedor you saw them in each other’s company at every opportunity. They journeyed to their school together and when the brooks were high with the Spring rains Fedor would always carry his companion over the water. In the winter, when snows were deep, it was Fedor who broke the path and it was he who always found the early spring flowers. In the summer time both drove the herds to pasture and if a sudden storm came up, it was Fedor’s coat that protected the girl from the raindrops.

Did other boys attempt to tease Martusja, it was Fedor who came forward as her protector and, one one occasion, when a boy pushed Martusja in the brook, it was Fedor who held her tormentor’s head under water until he cried for mercy even though the other boy was three years older than Fedor. At the dance, the other boys always looked to Fedor for permission before they claimed a dance with Martusja whose glance always sought Fedor’s eyes before assenting.

In the beautiful fruit garden that belonged to Fedor’s father the nightingale daily sang during the long summer months and Fedor learned the art of imitating birds. His warbled bird songs always brought Martusja to his side. The whole village knew and wagged its collective head saying they were created for each other. Even their parents gave silent assent and though the two lovers never spoke of their love one could not think of life without the other.

Chapter II

Fedor was twenty when he received the summons that made him a member of the Hussars. When the day came that he was to leave home to enter upon his new life it bought with it the parting with Martusja. Fedor asked for no promise neither was there one given for Fedor’s faith in Martusja was as deeprooted as the mountains. She would be waiting for him when he again returned to take his old occupation. There were few letters exchanged between sweetharts for letter writing in their country is not as common as it is in the new world. Intervals of two and three months elapsed between letters but in each Fedor inquired for the Mitrims family and asked how they did and it was understood at home in that his solicitude was for Martusja.

After the first year Fedor was granted a furlough and he came home, bringing with him a silk handkerchief and a ring with a red stone, which gifts were for his sweetheart. To the simple folks of the village the gifts signified the formal betrothal. This understood, it was noticed that after Fedor’s return to army life he always made mention of Martusja by name in his letters. For while there is no written law, either clerical or secular, on the matter of what constitutes a betrothal, certain customs have been adopted to which are given all the force of law. Fedor felt justified in feeling that Martusja belonged to him.

Letters came from his betrothed now and Fedor counted the days that intervened until the time he should be released from army life. But finally the interval between letters from home lengthened and Fedor could not understand Becoming impatient he wrote to his parents and asked them to explain the long silence: When no answer came he wrote to the parish priest and inquired whether his parents were living or dead. He did not mention the name of Martusja but the priest understood. Fedor’s father was called to the parsonage.

“Vasil, why don’t you write to Fedor?” “Why, Father, he will be home in six months and then he shall see for himself what has happened.” “You know it was not our fault.” “It is so” the priest replied, “but anyhow you should write.” “Will you be so kind as to write, Father?” Vasil inquired, “I fear to write what my boy should know.” “Good Vasil, I will write. For who knows but longing may overcome Fedor who may desert the army to see his beloved Martusja.” “It may so happen” replied Vasil, “be so good as to write and console him.” The pastor’s message to Fedor was brief. It read, “Thank God, all at your home all are well; when you come home you shall see for yourself.”

Finally the day came that brought Fedor’s release from the army. From the hilltop he saw his native village in the distance. As he drew closer he made out his old home and the home of the Mitrims nearby. His heart beat faster and faster as the realization came that soon he should see his Martusja. As he neared the mill which was owned by Jurko, the boy, whom in their school days he had choked because he teased Martusja. In front of the mill stood a woman but as he came in view she entered the mill. His heart gave a bound as he fancied a resemblance to his beloved. He would have entered the mill to inquire but for his old enmity of Jurko.

Entering the grounds that surrounded his old homestead he came on his father with a scythe in his hand. “Glory be to Jesus,” was Fedor’s greeting to his father who, not expecting his son’s arrival, trembled as with fear. When he could recover his breath he shouted, “Mother, our Fedor is home.” The mother heard and running from the house soon had her boy clapsed in her arms, kissing him again and again. Then came the meeting of brother and sister the latter clasping Fedor in her arms and showering him with kisses.

Chapter III

It was after the family party had gathered in the house that Fedor was told the story of the happenings during his absence. When Fedor had returned after his furlough, Jurko, whose parents had died, leaving him in possession of the mill, began to visit the Mitrim homestead. To Martusia he showed the many beautiful things left him by his parents including a number of golden ducats. He formally requested the girl’s parents for her hand in marriage. The mother of the girl told Jurko of Fedor who would claim her as his wife when released from army duty. “Fedor?” said Jurko in contempt, “why Fedor couldn’t give his wife even a good living on his six eights piece of land. Look at my fields, my mill. My wife would not need to go to the fields to work. She would not be required even to prepare a meal as such work would he done by my servants.”

While Jurko was speaking Martusja’s mother could not take her eyes from the gold laying on the table. It’s glitter seemed to fascinate her and steal hear heart. As from afar she heard the words of Jurko who was saying, “You will have everything you want. When you want flour you shall come to my mill and carry away what you want.” With these fair promises ringing in her ears the mother started to sing the praises of Jurko to her daughter. “O, Jurko, it would be good for her in your house. She would be better off than I in the house of my husband for I had never much of anything but work.” Jurko saw his advantage and when not observed slipped several of the golden ducats into the hands of Martusja’s mother. The feel of the gold brought the woman to his side. “She will be yours, so God help me” she whispered in the ear of Jurko.

After this the mother began at every opportunity to sing the praises of Juro to her daughter who was told how happy she would be in the home of the miller. When Martusja refused to give her consent to the match her mother beat her. Peace had fled from the once happy home and Martusja fled to Fedor’s mother for consolation. “Fedor will be home in a short time” she told the girl. Seeing this, Martusja’s mother began to quarrel with Fedor’s parents and made such a scene that the villagers came to look on. To Martusja she offered the alternative of marriage with Jurko or a mother’s curse. “I will curse you until the flesh falls from your bones and even the earth will give up your bones.”

The parish priest was informed and summoned Martusja’s mother to the rectory. To him the woman gave only a defiant answer. “It is not your business – she is not your daughter.” Jurko pressed his suit by presenting the mother with money and fine linens on every possible occasion. After Easter he sent to men to the Mitrims home to ask the hand of Martusja in marriage. The father of the girl gave them an answer in the negative before they sat down to the table. The girl’s mother, however, went from the house to seek Martusja whom she dragged into the presence of the men by the hair and promised the callers that she should be Jurko’s. Those formalities settled by the mother. Martusja went unwillingly to the church and only half- heartedly answered the questions put by the priest.

Wedding festivities were held in the mill but the bride’s father and sisters were absent. After the wedding Martusja did not live in the luxury promised by Jurko. He dismissed the servants and she was compelled to work alone. His mother-in-law was chased from his home when she called him to task for neglecting his promises. From that time on Martusja was a changed woman who shunned the village, not even attending church services. She rarely spoke and avoided all her old acquaintances.

Chapter IV

When all these happenings had been related to Fedor he arose from the table, his face ashen white and haggard, and made as if to leave the house. Mother and sister clung to him and begged him not to go out into the night. Their entreaties prevailed and Fedor remained in the home. Early the next morning he approached his father and requested that he be given enough money to pay his passage to America. “To America?” the father repeated sorrowfully. “Yes” replied Fedor, “I cannot stay any longer in this fillage and you surely do not want to see me go to prison.” “Remain here but until we finish the work in the fields,” the father requested. “No, I must go,” his son answered. “Wait, then, until I raise enough money for your trip” the father replied.

On the third day from that conversation Fedor vanished taking with him only a few articles of clothing. His father had expected that Fedor would forget his love affair and had postponed complying with his request for money until Fedor had time to get over the effects of his great disappointment. Fedor has told no person of his plans nor had he gone through the formality of leave taking. Family and friends looked for his early return and only feared he might attempt to harm Jurko who had stolen his betrothed.

When Fedor left home he had with him a few crowns which brought him to the nearest city. Here he obtained work on a railroad and money earned paid his way to Prussia where he remained to months earning the money to pay for a passage to America, the land of promise.

On his arrival in New York he was offered employment by a western farmer and for twelve long years he worked as a farm laborer in a western state. After the farmer died, Fedor came east and obtained work on a farm in Pennsylvania. One day he was sent to the nearest town to purchase some things for the farm and while walking along the street over heard two men conversing in the Russian language. Seventeen years had elapsed since he had heard a word spoken in his mother tongue and he almost cried from happiness. He followed the men who entered a church and Fedor decided to enter, seating himself in a rear pew. He saw that everything in the church was similar to what he had seen in the church in his native village even to the Ikonostaz flags. Only the people were different being better dressed than those who attended the village church.

The services began and he saw at once that they were the same as those at which he had so often assisted in the homeland. He noticed that while there were many women present only a few men were in attendance and he was reminded that it was not Sunday. It must be some holiday, thought Fedor, and the men are working. What festival was being celebrated he could not ever guess for long residence among American Protestants had caused him to forget the dates of church holydays. All during the services his thought wandered homeward. He thought of his parents, his sister and of Martusja, his first love. And although he tried hard to forget thoughts came unbidden to his mind. Where were they all? Were his parents still alive? Was Martusja happy in the home she had made with Jurko? Tears started to stream down his face, and sobs half stifled shook his frame. The man next to him in the pew noted his sorrow but refrained from asking him any questions until the services had ended. At the church door he looked into the face of Fedor and recognized him. “You, Fedor?” Fedor made an attempt to pass his inquisitor but the man barred his way. “Don’t you know me, Fedor? My name is Peter; we played together and went to school together. Come, let us go where we can talk without being disturbed.” Peter began to talk about happenings in the village.

When Fedor disappeared everybody thought he would attempt to do some bodily harm to Jurko who had taken his Martusja. Jurko began to worry and took to drink. In one of his drunken spells he was struck by the mill wheel and killed. He left everything to Martusja who remained alone at the mill after his death allowing no one to visit her not even her mother. Martusja finally pined away and went on a sick bed from which she never arose. Before she died she requested Fedor’s sister, Nastja, who had married, to convey word to Fedor if he was ever located that she had been faithful to him until death. To Fedor she left the mill and all her belongings even though the villagers all believed him dead long since.

Peter also told of the death of Fedor’s parents and related how Martusja’s mother was found cold in death on the grave of the daughter she had so cruelly wronged. Fedor listened to the recital of his companion in silence while his heart grew heavy as news of loved ones was told. His anger toward the woman he had loved and lost was gone and was turned on himself. Why hadn’t he listened to his father and remained at home? In two or three months life would have had a different outlook. But he thought of his feelings toward Jurko. Even after all these years fierce hatred of the man who had robbed him of his boyhood sweetheart came unbidden to his heart. Peter glanced at the drawn face of the man and grew afraid. He broke the silence by saying, “Do you know, Fedor, in a few months I am returning to the old village. It is time I should see it again after four long years. Suppose we go together?” “What for, Peter? I have nothing there, now.” “To claim the mill and the money left you by Martusja.” “That money does not belong to me and besides it is money cursed.” “Come if only to see your old home,” pleaded Peter. “You are right,” Fedor said finally, “I will come to you, Peter, and make the necessary preparations.”

Fedor inquired as to the dwelling place of Peter and in two days came to meet him. Both went together to the consulate where a testament was drawn up in which Fedor directed that his father’s property be given to his sister, Nastja. The property left him by Martusja he directed should be sold and the money realized from the sale should go toward erecting a monument on her grave, the balance to go to the church and to the poor of his village. From that day onward Peter lost all track of Fedor.

Chapter V

Fedor Bistrica came to our town and rented rooms in a Second Alley basement. He was a quiet man who seldom spoke and mingled but little with the neighbors. His visits to the saloons where the men of the neighborhood congregated where infrequent and he made but few acquaintances. His monthly dues he, himself, brought to the church as if to forestall a visit from the collectors. His rooms in the basement were poorly furnished, the furnishings including a bed, small cook stove, table and trunk.

Despite his humble surroundings and lonely life, Fedor did not fall into any careless, bachelor ways. Everything about his abode was neat and clean. His working clothes and other wearing apparel he washed during his leisure hours and what needed extra starching he had sent to the laundry. His frugal meals were cooked over the stove in his kitchen and thus he pursued the even tenor of his way. It was early that the neighbors noted that the lonely bachelor avoided women and children and Fedor was content that it was so because he had come to believe that he hated both. When the people who resided on the upper floors were not fighting among themselves they were playing various musical instruments.

When Fedor tired of the noise he made for the hills if it were summer time or took long walks on unfrequented streets, when the weather got cold. One day Fedor noticed unusual activity about the home of his neighbors, the Italians, and he learned that they were moving. That night he speculated on what kind of neighbors the new tenants might prove to be. He soon learned that a young couple with a little girl of about three years had taken up residence in the house. Fedor noted that the couple displayed more than the accustomed amount of affection. Every morning, before departing for work, husband and wife exchanged a parting kiss and when the child was present he could hear her childish treble lisp a “Goodbye, Papa.”

In the evening he heard sounds of merriment coming from the home and on occasions when all sat outdoors he noted other signs of love and contentment which might not be so apparent to eyes less observant to his and it seemed to him as if the happy family took pains to conceal their happiness from an envious world. At such times Fedor was won’t to glance about his own lonely home and ask himself whether it was possible for others to feel so much happiness when he was compelled to endure only sorrow and misery.

On occasions when Fedor heard words spoken in his own tongue he always made an effort to avoid the speakers. However, one day he heard the young husband in the room above him address his wive as “Martusja, my heart and my life.” The roar of a passing train drowned out the rest of the sentence. “Martusja!” What memories that aroused in the heart of the lonely man. He had noted that the husband spoke the name caressingly as he himself might have spoken it in the old days to his Martusja. How long ago those days seemed now. The old sorrow again came gnawing at his heart. Had he only listened to the advice of his father. But, then, what if he had met and revenged himself on Jurko? How he might have been living how with his Martusja and their children. He again became envious of the whole world and as seraps of conversation again came to him from the upper floor he put on his hat and coat and went out.

The months passed and Fedor noted that the child on the floor above seldom cried as is the way with children. He felt that the little one was too happy. His envy continued and he carefully avoided the happy couple. Eastertime drew near and the warm, beautiful days of Spring came again. Fedor had been working on the night shift and had just finished his breakfast. He noticed the young wife depart from her home apparently on a shopping trip to a nearby shore. He heard her promise the little girl to buy some nice things at the store and saw her stoop and kiss the child. The sight caused a tug at his heartstrings and he mentally resolved to seek new quarters. Fedor was about to open the door when he heard a timid knocking on the panel. He opened the door and saw standing on the threshold, smiling up at him, the neighbor’s little girl. The child walked into the room confident of a welcome and the astonished man permitted her to do as much as she pleased. It was his first visitor since he had come to live there. The child took a piece of bread from the table and began munching it. Turning hear gaze on Fedor she required, “Uncle, did you have breakfast?” Fedor gave the child his watch to play with and after examining it and listening to its “tick-tick” she opened the door, “Bye-bye, Uncle” she said, as she backed out of the door, throwing him kisses all the while. Tears came to Fedor’s eyes. “I must leave here” he muttered to himself.

Two days later he again heard the knocking on his door and this time he knew it was his little visitor again demanding admittance. It was raining and Fedor decided he must admit the child. This time she came with one shoe and one stocking in her hand and in her childish way demanding that Uncle put on “my shoe and stocking.” After warming the shoe and stocking at the kitchen fire, Fedor took her in his lap and put them on. The little girl told him that her name was Helen, that her mother had gone to the store to buy her Easter eggs and candy. She put her little arms around Fedor’s neck and was saying, “I love you, Uncle” when the door opened and Fedor saw Helen’s mother in the doorway. The mother did not know Fedor other than to hear the neighbors say that he was a queer fellow who never speaks nor visits anybody. She became confused and not knowing what language to address her queer neighbor made excuses in poor English and took away little Helen who turned and said, “Bye-bye, Uncle.”

Fedor, after they had left, felt angry with himself and with his neighbors of the upper floor. However, he could feel the agreeable warmness of the child’s kisses which secretly pleased. But Fedor was determined he should continue the hermit and put on his hat and coat deciding to look for other living quarters. Finding suitable quarters for a bachelor was not an easy task and Fedor returned home without having accomplished task. He decided that his door would remain closed even to little Helen.

Chapter VI

On the Friday before Palm Sunday Fedor was making a fire in his stove as the day was cold and damp. Again he heard the knocking on the door but he steeled himself to ignore the invitation contained in that knock. The child began to pound on the door and when it didn’t open he heard sobbing. Then he heard Helen’s mother descend the steps and heard he say, “Dearie Mine, why did you go out on such a day without stockings or shoes? You will catch cold.” Fedor felt ashamed for having been so cruel as to refuse the child admittance. He would be at fault if the little girl did catch cold an ddie. The poor little girl who loved him and who never did anything wrong. Am I a Christian? he asked himself. Even a dog would be permitted to come in the house on such a day. His only consoling thought was that the young mother might not have known he was at home.

That evening he heard the step of the husband as he returned from work and as he entered the door he heard the wife say, “Our child is ill, go right away for a doctor.” Later he heard husband and doctor arrive. On Palm Sunday he attended church services bur could hardly wait for the end of the service. He went directly home although it was a beautiful day and remained in the house the entire day. He noted that the doctor came twice to see Helen. He felt miserable and the next day decided to remain away from work. He took a walk on the main street and noticed that the stores were crowded and that Easter bunnies and candy were displayed in the windows. As if driven by an unseen hand he went into a store and purchased the largest Easter bunny he could find and returned home.

About noon time he determined he could stand it no longer and would see his little sick friend. Taking the box with the bunny he entered the home of this neighbors. The kitchen was deserted but in the next room was a little white bed upon which Helen was lying. At her side were the anxious and sorrowful parents. “Glory be to Jesus Christ” was Fedor’s greeting as he entered the sick room. Both parents stood up and looked at Fedor who felt their looks might have been directed at their child’s murderer. After a moment, Nikola, Helen’s father, responded to the greeting, “Forever, Amen” and then inquired, “Are you Russian?” Fedor understood their former silence and said, “I came to see Helen, if you do not object?” “May the Lord pay you for your kindness – the child loves you and asks after “Uncle.” After Nikola had shooks Fedor’s hand the visitor felt better and thought, “They do not know it is my fault that the child is ill.” “Tonight comes the crisis in her illness” they told Fedor. Even then the little patient babbled in her fever, “Mother,” “Father,” “Uncle,” “Open.” Fedor felt conscience stricken that he had not opened the door for the child. He took the box containing the Easter bunny, and Easter egg. “Helen, dear, see what your uncle brought you, a white bunny and Easter egg. The child opened her eyes and recognized him with a warm smile. She took the bunny and the egg and turning over fell into a deep sleep. The mother rejoiced for the doctor had said after a sleep the worst would be over. She, in her gratitude, took Fedor’s hand and kissed it. He advised the parents to seek some rest saying he would watch over the child until morning. Both thanked him and sought a much needed rest. Fedor’s vigil continued for two nights and when he saw that all danger had passed he again returned to his own rooms. When he arouse in the evening Nikola came to his door, “Helen is up and playing and wants to see you; can you come up for a few when Helen saw him she cried, minutes?” Fedor came quickly and “Uncle, Uncle, here is the Easter bunny and the egg” and came to sit in his lap. “Wait, Helen, dear” said the mother, “I must give uncle some supper. You will not refuse, Mister? She did not even know his name. “We do not even know the name of our benefactor” Nikola said, “You must excuse the meal. This being the last week of Lent we have not meat” the woman explained.

All took their places at the table and Helen asked to be seated near Uncle. After the meal little Helen was put to bed and in a few minutes was sound asleep. “We were married in the old country,” the wife explained to Fedor. “Nikola worked for many years on the parson’s property. Our parents were not in favor of the marriage so we decided to come to America. My mother’s brother is here somewhere in America but although we have advertised in the newspapers we cannot find him.” A thought came leaping to Fedor’s mind. “Is it long since your uncle came to America?” “About twenty five years since” she answered. “Are you not from Poland?” asked Fedor gazing intently into the woman’s eyes. “How do you know?” asked both at once, wonderingly. “You are the daughter of Nastja Bistrica? Fedor could not stand it any longer and he buried his face in his hands and wept.

Martha knew now who he was and taking his hands she looked him full in the face and inquired, “Uncle?” After a short pause Fedor looked heavenward and said, “O how merciful is the Lord. He has performed a miracle that I might know and find myself.” Walking to the beside of the child he took little Helen’s hands and kissed them as if they were the hands of an angel.

.jpg)